Kings, brave heroes, beautiful women, dangerous journeys, battles, fearsome dragons and otherworldly.The geographical range of Viking exploration between the 9th and 12th centuries AD was amazing.

This course provides an introduction to the myths and sagas of medieval Scandinavia. Disclaimer: The information on this page is provided as an overview. The course outline, readings, and assignments may be subject to change in the final.

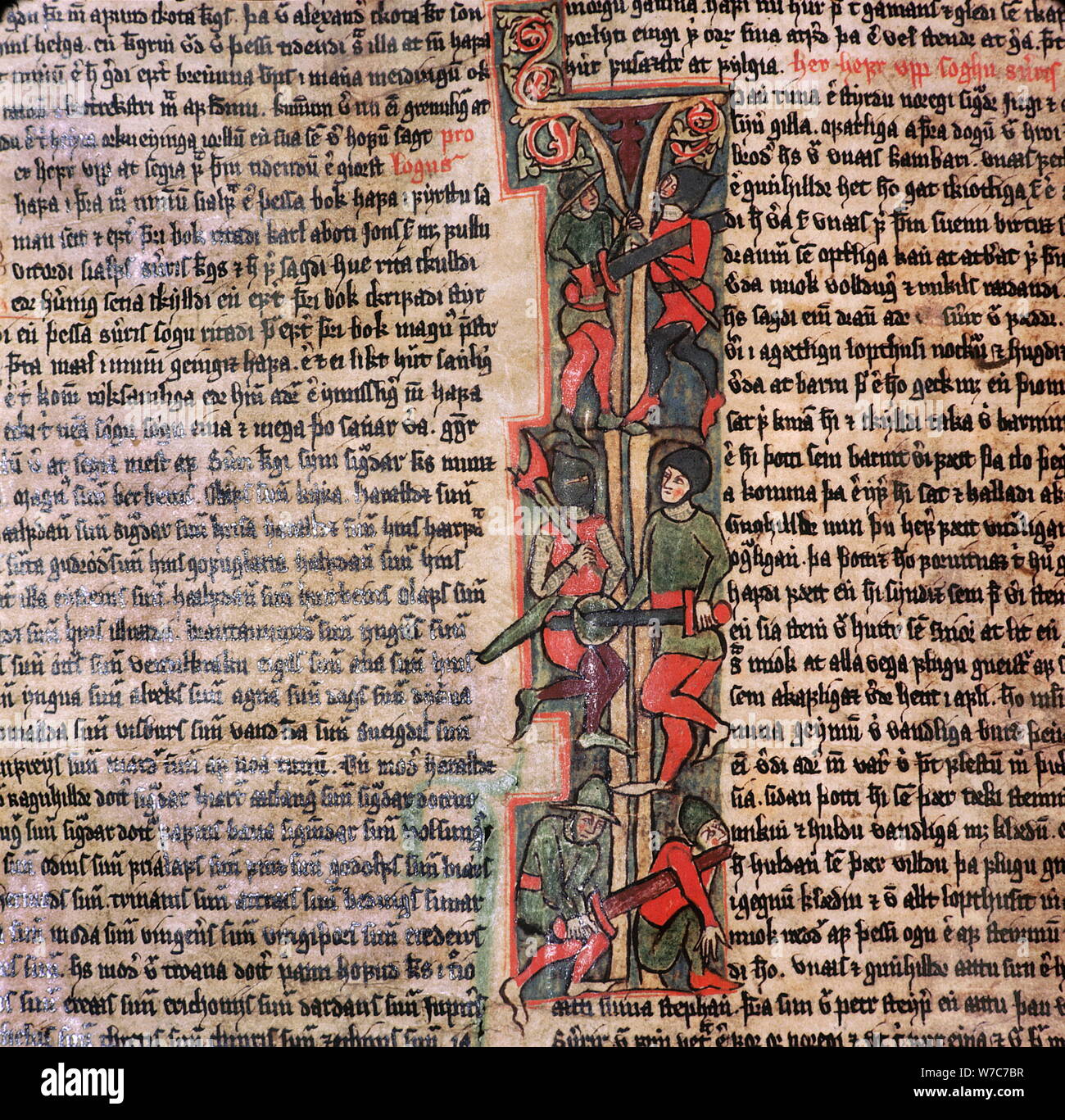

A saga character with such a name will frequently have the qualities associated with this.Their descendants in their North Atlantic colonies make up the modern populations of Great Britain, Ireland, France and Iceland. In Eastern Europe they gave their name to the lands of Russia and Belarus and in Western Europe to Normandy.Their advanced seafaring skills and longships extended their reach to Southern Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia, and helped establish settlements as far west as Greenland and North America.They sailed Europe and Asia’s seas and river systems to reach the great cities of London, Paris, Rome, Baghdad, Jerusalem, Alexandria and Constantinople, the glittering capital of the Byzantine Empire.To the Anglo-Saxons they were the Nordmenn or Dene (Norwegians or Danes), to the Irish they were Dubgaill and Finngaill (dark and fair foreigners). To the Franks they were Nortmann (north men) and to the Germans they were Ascomanni (ashmen, from the ash wood of their boats).

LESLIE-JACOBSEN‘Blood flying and brains falling like rain’: Chivalric Conflict Gone Norse — INGVIL BRÜGGER BUDALFrom Oral to Written in Old Norse Culture: Questions of Genre, Contact and Continuity — ELSE MUNDALBook History, Manuscript Studies & PalaeographyPalaeography, Scripts & Manuscript StudiesMedieval & Modern (Indo-European) Languages & LiteraturesGermanic langs & lits (other than English)North Germanic/Scandinavian languages & literaturesComparative & cultural studies through literatureMedieval & Renaissance History (c. MULLIGANTraversing the Space of the Oral-Written Continuum: Medially Connotative Back-Referring Formulae in Landnámabók — SLAVICA RANKOVIĆǪrvar-Oddr’s Ævikviða and the Genesis of Ǫrvar-Odds saga: A Poem on the Move — HELEN F. 1150) — JONAS WELLENDORFLetters, Networks, and Public Opinion in Medieval Norway (1024–1263) — LEIDULF MELVEGyrðir á lykil (Gyrðir owns the key): Materialized Moments of Communication in Runic Items from Medieval Bergen — KRISTEL ZILMERMoving Lists: Enumeration between Use and Aesthetics, Storing and Creating — LUCIE DOLEŽALOVÁTalking Place and Mapping Icelandic Identity in Íslendingabók and Landnámabók — AMY C.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)